1. Herr Professor and other academic refugees from the Nazis: can you stay neutral?

Warburg Institute, Woburn Square Garden

Academic refugees and the Academic Assistance Council

The history of refugees from the Nazis can be divided into two periods - before and after 1938, the year Hitler annexed Austria and conducted the November Pogroms or Kristallnacht. By the end of 1937 only about 5,500 refugees had arrived in Britain, the other circa 70,000 arrived between March 1938 and September 1939.

Universities were among the earliest supporters of refugees, albeit only academic refugees, because university lecturers were amongst the first to loose their jobs when the Nazis came to power. In response, William Beveridge, Director of LSE, founded The Academic Assistance Council (AAC) in May 1933.

The Council provided small grants that allowed the refugees to continue their work at universities in Britain for two years, hopefully enabling them to find a more permanent job. Grants were strictly limited to those who had the best chance to get a job, i.e. more established academics with an international reputation, not too inexperienced and young, not too old. Others were told to find work in industry or look into teaching posts.

By July 1935 University of London had provided 55 temporary teaching or research posts to refugee academics, more than any other British university. Eventually about 2,000 people were helped. The impact on the universities was considerable, from areas in which Germany had traditionally been strong, such as classics, history, and the natural sciences, to subjects which had not been established in Britain yet, such as art history and psychoanalysis.

The AAC was initially seen as a temporary measure, and it was keen to be seen as unpolitical. Their founding statement emphasised:

Until the November Pogrom many academics strove to keep their scholarly connections with German peers, trying to remain neutral and objective, condemning racial persecution yet continuing to work with colleagues who were adopting Nazi ideology.

But in 1936 the AAC became a permanent organisation, changing its name to the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning. From 1937 until the outbreak of war its offices were at the heart of academic London, in 6 Gordon Square. It still operates today, under a new name, CARA – the Council for At-Risk Academics.

All eminent scholars who were helped that are listed on the organisation's website are men. However, the British Federation of University Women created an Emergency Sub-Committee for Refugees in May 1938. They collaborated with the Esther Simpson of the SPSL to bring across several hundred women scholars. Many professional organisations helped their peers in Germany and Austria, thus there are documents recording their assistance scattered across London, part of the organisational archives.

The Warburg Institute

The Warburg Institute was a particular beneficiary of the AAC. The Institute’s founder and many members of staff were Jewish and the director Fritz Saxl was very quick to realise that there was no future for them in Germany under the Nazis. The whole institute, people, collections and furniture, came to London on two boats in December 1933. They got permission to leave by stating it would be a loan for three years. Finances were by no means guaranteed and the director was keen to deflect any concerns about the institute being a German enclave where staff did not speak English. From 1939-1943 they organised 4 very popular exhibitions, one of which travelled across the country for 2 years, utilising their huge photographic collection. Their efforts paid off when the Institute became part of the University of London in 1944. The Observer newspaper called it ‘the best Christmas present from Hitler’. It moved to its current, purpose-built premises in 1958.

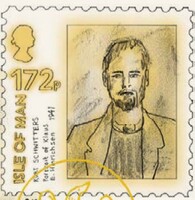

Klaus Hinrichsen

In 1937, Klaus Hinrichsen was one of the last Jewish students to receive a PhD in art history. Being half Jewish he was unable to get work in his field yet he could still be conscripted into the German army. To escape conscription he moved to London in 1939. Interned on the Isle of Man in 1940 he organised cultural events in the camp and met acclaimed artists. After the war he worked in pharmaceuticals but he retained his interest in art. In retirement he became the foremost expert on internment art.

The image included here is adapted from stamp art issued by the Isle of Man featuring internment art, 2010. Learn more about archives which include Hinrichsen's papers.

We exit Woburn Square Garden onto Gordon Square. We cross the road, turn right, and walk east to Tavistock Square. Follow the walk