2. Basque refugees from the Spanish civil war: the issue of childhood exile

Tavistock Square

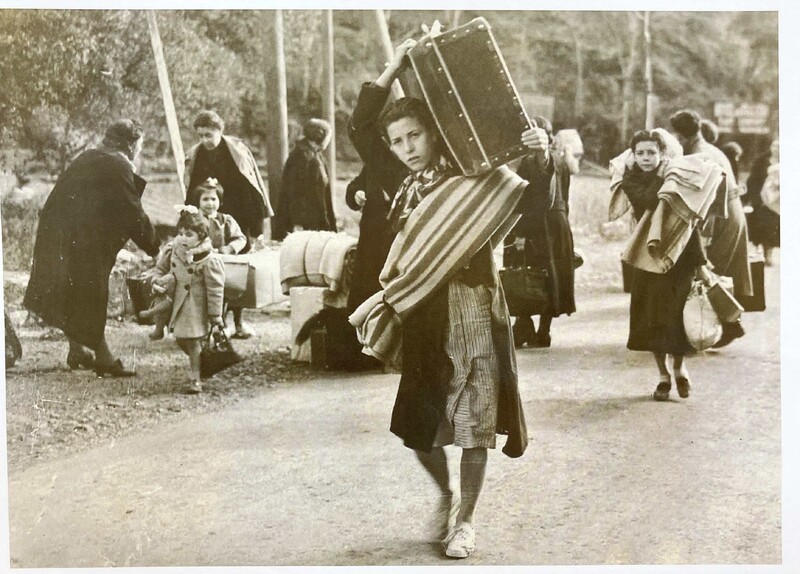

Even while trouble was brewing in Germany, civil war broke out in Spain. Following the bombing of Guernica in 1937, residents of Bloomsbury read newspaper reports of Basque refugees, including children, fleeing over the Pyrenees and into France. The plight of this group of refugees caught the sympathy of British people and led to calls to settle some of the children far away from the fighting, in the UK.

Virginia Woolf, whose nephew Julian Bell was killed while working as an ambulance driver in Spain, wrote in her diary that she saw Spanish refugees crossing Tavistock Square:

As I reached 52 [Tavistock Square], a long trail of fugitives - like a caravan in a desert - came through the square: Spaniards flying from Bilbao, which has fallen, I suppose. [...] A shuffling, trudging procession, flying—impelled by machine guns in Spanish fields to trudge through Tavistock Square, along Gordon Square, then where? —clasping their enamel kettles.Virginia Woolf, 23 June 1937, The Diary of Virginia Woolf, ed. Anne Oliver Bell (London: Granta, 2023) Access this at Senate House Library

Bringing the Basque children to the UK

It was difficult for refugees to enter the UK at this point, but in May 1937, a joint committee of charity organisations and private individuals, including the Quakers (based in the north of Bloomsbury on Euston Road at Friends House) worked together to bring c. 4,000 child refugees from Spain into the UK. It was a scheme similar to the Kindertransport which began a year later - notably, both of these schemes were over the objections of the British government.

In agreement with the Spanish Republican Government, and the children’s parents, the Basque children came to the UK and were kept together in small ‘colonies’ of between 20 and 40, housed in various parts of the country, and looked after by local wardens alongside Spanish teachers who had fled with the children. In this way, they could retain their Spanish identity. Quakers in Britain, particularly the Rowntree and Clark families, provided support to the unaccompanied children, and many ran colonies, including one in Colchester, in Essex, and one in Street, in Somerset.

It is possible that the people Woolf saw in Tavistock Square were in transit, from one London railway terminus to another perhaps. The Basque children did not settle in Bloomsbury – though some of the colonies were in London, these were generally in the outer boroughs. Moreover, the children did not stay anywhere in the UK for long. They were not orphans and – unlike the Jews in Nazi territories – they were not unwanted by the political regime in Spain. Once Franco came to power, he demanded their return, characterising the scheme as a violent stealing of the children from their homeland by foreign nationals interfering in Spanish business. Most of the children were back in Spain within six months.

Bringing relief to displaced people in Spain

In fact, the Quakers’ Spanish Relief Committee had never fully supported the scheme to bring the children to the UK, and there was disagreement between Quakers in Britain about it. Since the beginning of the Civil War, Quakers had been working in Spain, supplying canteens and refuges with milk, and helping to set up colonies for displaced children in Spanish countryside, away from the fiercest fighting. Alfred Jacob, a Quaker on the ground in Spain, believed it was cheaper to bring the food to the children than the other way around: supporting relief work in-country would bring about ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’. He was critical of private individuals in Britain wanting to adopt Spanish babies, and felt that evacuating just some children out of the multitude that needed aid was ethically difficult. He also worried about the psychological impact of removing young refugees.

Norma Jacob, Alfred's wife, advanced other reasons for helping the children in their own country. She believed the Spanish colonies were the only hope for a peaceful future for the country: the friendly relationships forged in these colonies, with refugee children and caretakers from many parts of Spain, might have the power to help rebuild a country shattered by civil war.

Afterlives

In 2012 it was the 75th anniversary of the sailing of the Basque children for the UK, and the Guardian interviewed one of the child refugees who never returned to Spain, Herminio Martinez. His testimony reminds us of the psychological impact of leaving one’s homeland as a refugee, especially as a child:

I am of that Spanish generation that never was, the Spain that never flowered because it was cut off. Life has been very interesting, but I still have within me a sadness, a loneliness. In essence, I don’t belong.The Guardian, 11 May 2012, Forgotten children of Spain's Civil War

To the north of Tavistock Square is our next stop - Woburn House. Follow the walk