Education: The Black British Experience (Then and Now)

- Title

- Education: The Black British Experience (Then and Now)

- Date

- 26 March 2025

- Description

-

"Education: The Black British Experience (Then and Now)” delved into the significant historical and contemporary challenges faced by Black British students in the education system. This event explored the practice of wrongly labeling black children as ‘educationally subnormal’ in the 1960s and 1970s. It reflected on the emergence of supplementary schools as a vital response to these challenges and the key role they played in providing culturally relevant education and support. Our speakers brought us up to date on ongoing disparities and aimed to fostered a constructive dialogue around strategies for future success, emphasising the importance of community and parental involvement, advocacy and innovative educational practices.

We hope this vital conversation contributed to conversations around the empowerment of future generations and the desire for an educational system that brings out the best in all students.

Speakers

Professor Gus John (co-founder of CEN)

Maisie Barrett (ESN school survivor, author, and activist)

Dr Nkasi Stoll (Researcher, mental health, and well-being of Black students in Universities)

Dionne Campbell-Mark (Advocacy Manger and Parent Co-ordinator, CEN)

Professor Gus John is a writer, education campaigner, community activist and life-long Pan-Africanist, a learning facilitator, and management consultant. He co-founded the first Black Supplementary School in Oxford (Cowley and Blackbird Leys) in 1966 and Birmingham (Handsworth) in 1968. He was Britain’s first Black Director of Education and Leisure Services. John chaired the Black Parents Movement (Manchester) and co-founded with Gerry German, the Communities Empowerment Network (CEN). He is author of several books including The Crisis Facing Black Children in the British School System (2003), Taking A Stand: On Education, Race, Social Action and Civil Unrest, 1980-2005 (2006) and more recently Don’t Salvage the Empire Windrush (2023).

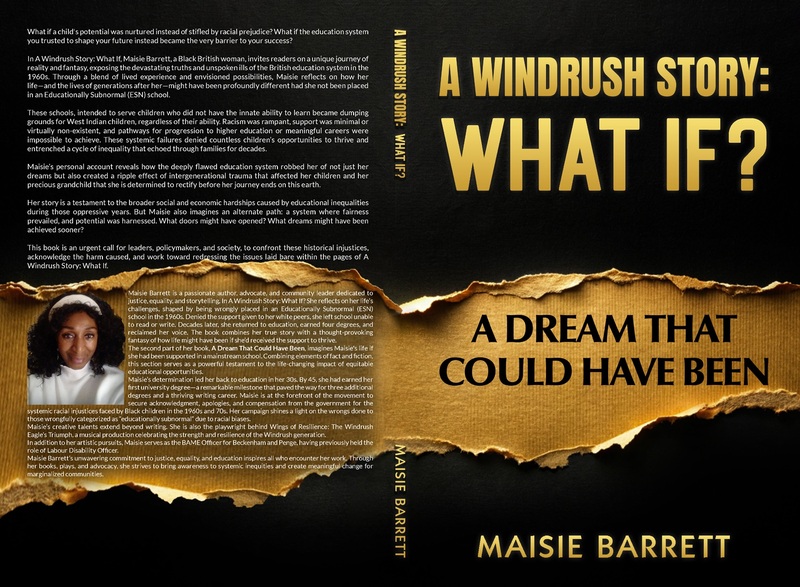

Maisie Barrett is a passionate author, advocate, and community leader dedicated to justice, equality, and the power of storytelling. Featured in Steve McQueen’s documentary “Subnormal: A British Scandal,” She overcame systemic racism in the British education system. Her experiences inspired her to write Subnormal: How I was failed by the British Education System and Colonial Family (2023) and A Windrush Story: What If? (2025), a fantasy scenario exploring how her life might have been different if she had received proper educational support. Despite early setbacks, Barrett earned four university degrees. She is also a prominent figure in the campaign to secure acknowledgment, apologies, and compensation from the government for the systemic racial injustices faced by the children of her generation. Barrett’s book will be available for purchase and signature on the day of the event.

Dr Nkasi Stoll is a qualitative researcher who specialises in understanding and tackling race, health and education inequalities. She completed her PhD in Psychology at King's College London, which focused on exploring the racialised experiences and institutional factors that impact Black undergraduate and postgraduate students' mental health and wellbeing. She has experience working on research studies and within clinical services to improve the lives of children, young people and their families who present with mental health struggles. She is also the co-founder of Black People Talk, a not-for-profit, that runs peer wellbeing support programmes for Black university students.

Dionne Campbell-Mark is an Advocacy Manager and Parent Co-ordinator for the Community Empowerment Network (CEN). Campbell-Mark worked for over twenty-years in the the civil service Department for Communities and Local Government, where she gained experience in project management and policy. She took redundancy in order to support her child’s education, complete a diploma in counselling and train as a teaching assistant. Her concern with education was taken a step further when she became Chair of the George Mitchell School’s Local Governing Board. Her experience in the education sector has enabled her to develop strategies for success.

This event was chaired by Dr Juanita Cox. Cox is Black British History Community Engagement Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research (IHR) and co-curator of the Senate House Library exhibition In the Grip of Change: The Caribbean and its British Diaspora. She was Research Fellow on the three-year AHRC funded ‘The Windrush Scandal in a Transnational and Commonwealth Context’ project and the earlier scoping project, ‘Nationality, Identity and Belonging: An Oral History of the Windrush Generation and their Relationship to the British State, 1948-2018’. Her publications include When Home is a Hostile Environment: Voices of the Windrush Generation and their Descendants (2024). She also has a passion for Caribbean literature and is currently the leading authority on the life and work of Edgar Mittelholzer (1909-1965) and editor of the compendium, Creole Chips and Other Writing (2018). She is a trustee on the board of the Oral History Society, co-founder of the ground-breaking series, Guyana SPEAKS and on the editorial board of Black Histories: Dialogues.

-

A Life-Changing Opportunity

Just before my 41st birthday, an extraordinary event transformed my life. I received news I never dreamed possible: UCAS contacted me with an unconditional offer for a BA degree at what was previously North London University, now London Metropolitan University.

At first, I understood the term "offer" but was unfamiliar with "unconditional." Once I looked it up, I was overjoyed. I was going to university! I would study a combined degree in Caribbean Studies and Creative Writing—two subjects I was passionate about. However, apart from creative writing, Caribbean Studies wasn’t my first love.

A Childhood Dream

As a child, I dreamed of becoming an actor. At the time, I didn’t realize I had a natural talent for creative writing, as I could only write in my head when I was 10 years old. This leads to an essential question: Why weren’t my creative talents nurtured? Or more fittingly, who stole that little girl’s dreams?

Suppression of Creativity in Education

In the late 1960s, George Land conducted a NASA-linked study to measure the creative potential of 1,600 children aged 3–5. Initially, 98% of the children scored at a genius-level. However, by the time they reached adulthood, only 2% retained this level of creativity.

Land’s findings suggest that traditional education systems suppress creativity rather than fostering it. Now consider this: if traditional systems suppress creativity, what happens to a creative child, not considered the brightest, placed in an environment like an ESN school where no learning occurs?

Sharing My Story: The Narrative of What If

My name is Maisie Barrett, and I stand here to share my deeply personal journey, woven into the narrative of my book, What If.

Part One: A Painful Reality

The first part of my book describes the devastating effects of being labelled educationally subnormal (ESN) and placed in an ESN school, despite my intelligence and creative abilities. This experience profoundly impacted my life and that of my children.

Part Two: An Imagined Dream

In contrast, part two imagines a hopeful alternate reality. In this world, a compassionate teacher recognized my potential, provided extra support, and guided my parents on how to nurture my abilities at home. In this version, I thrived academically and built a career in the Performing Arts as a performer and writer. This fantasy is inspired by truth: I had the ability to learn and excel, given the right environment and support.

My book also includes real-life case studies of children who struggled academically but achieved success with the proper support. These stories show that my fantasy was close to a "Dream That Could Have Been." Which was having a good education to thrive and pursue my dreams as an actress and writer.

Black Migration and Racism

The Windrush migration is part of a long history of Black movement to the West from the Ice Ages. Many Caribbean people saw their relocation to England as a move between parishes within the British Empire. However, upon arrival, the harsh reality of racism hit.

Though some were recruited as nurses or bus drivers to rebuild the economy, others—especially children—were not welcomed. Racism affected housing, employment, and education, rooted in pseudoscientific beliefs about Black inferiority. This prejudice led to many Black children, including myself, being placed into ESN schools.

My Experience in an ESN School

At six years old, in 1965, I was placed in an ESN school. Like countless other Black children, I was forced onto a different path. In this environment, like the nurses who were asked to come to Britain to work, I was the nurse looking after the poor white children who came to school unwashed with nits in their hair. When I wasn’t being a nurse, we traced letters, played games, did PE, and listened to stories, day after day, month after month, and year after year. There was no curriculum or structured education to prepare us for exams like the 11-plus.

At 16, we were expected to leave school unprepared for life. I struggled to fill out even basic job applications. At 17, I briefly worked winding thread onto bobbins, but boredom drove me to leave by my first break time.

Leaving School: Illiteracy and Isolation

When I left school at 15, I was illiterate and unaware of my lack of confidence and self-esteem. I entered a society where most individuals had received mainstream education, even if they were at the bottom of their class. Everywhere I went, I felt like the odd one out. I had no friends. Labelled as the illiterate girl with nothing interesting to say and a limited vocabulary, I became very quiet.

I had once been a confident performer as a little girl, entertaining children and teachers when I first entered the ESN school. However, by the time I left, all I had was an unattainable dream of becoming an actor—a "Dream That Could Have Been."

A Beautiful Black Rose in a Harsh Environment

While Britain's economy blossomed like a beautiful white rose in the early 1970s, thanks to the contributions of West Indians and others from the British colonies, my personal growth was stifled. At the time, I was a beautiful black rose, uprooted and placed in an environment that deliberately deprived me of the support I needed to grow strong branches and produce healthy black roses for future generations – my children.

The loneliness I felt during these formative years was overwhelming. Naively, I believed having children might fill the void—a grave mistake. I had nothing to offer my children but the painful echoes of my own childhood traumas.

A Loud Echo of Discourse

A miraculous event occurred when I was 13, though its full impact would not be felt until 50 years later. In 1971, Bernard Coard’s book, How the West Indian Child Is Made Educationally Subnormal in the British School System, sparked discourse in West Indian communities across England. These conversations gave voice to concerns long held in silence and, eventually, gave me my own voice.

This dialogue likely prompted my mother to question why her "Black Rose" still couldn’t read at the age of 12. Despite helping me memorise a few pages of the Bible, she recognised that I couldn’t read independently. My mother sought help from a Black Educational Psychologist who assessed me and declared, “Maisie is intelligent.” Until then, I had been labelled backward, even by my family. The psychologist promised my mother she would get me out of the ESN school—and she kept that promise.

Transition to West Park Girls' High School

I eventually attended West Park Girls' High School in Leeds, where I was placed in the lowest class. This was where I realized I was different. At 13, I was introduced to subjects like English, history, and geography for the first time. However, my classmates often tried to bully me, perceiving me as the odd one out.

This hostility led me to become defensive, a trait that still persists if I sense others view me as inferior. I attempted to make peace by offering sweets, new clothes, or even fighting their battles, but when that failed, I stopped attending school altogether. They couldn’t understand why I couldn’t read or write, or why I found them too noisy and often told them to "shut their mouths."

When I officially left school, I didn’t even realize it. I had no direction and no desire to settle for a job as a cleaner—I was too ambitious for that.

From Potential to Lost Opportunities

I felt like a discarded product, shaped by a racist education system that denied me meaningful education. The irony is that with proper education, we could have contributed positively to the economy. Instead, the system ensured many of us ended up in mental health institutions, prisons, or care homes—costing the government far more to fix the damage caused by neglect than it would have cost to educate us.

John B. Watson’s theory on the power of environment resonates deeply: “Give me a dozen healthy infants...and I’ll guarantee to mould any one of them into any type of specialist…” However, the ESN schools seemed designed not to create specialists but to consign Black British students to lives of unemployment and institutionalization.

Had I received a proper education, I could have attended university to study Performing Arts between 19 and 21, becoming a taxpayer and raising independent children capable of contributing to society. Instead, I became a lonely, illiterate mother, obsessed with learning in my thirties with no confidence to pursue my childhood dreams and had no idea what job I could do to make a difference in my life. My first real job was a chambermaid in a hotel that only lasted for 6 months, and it was my friend who helped me to fill out the job application form when I was 26 years old.

By the time I got to university in my forties, I was a mature student who didn’t even know the word, unconditional”, During this time, two of my children were institutionalised, due to mental health issues.

The Ongoing Legacy: "This Black Condition”

Mental health issues, poverty, and an unhappy mother—factors beyond just the absence of a father—have shaped this "Black condition." My son’s hospital care costs the government £350–500 per day, while my daughter’s care home costs £165–200 daily. My grandchild, too, is a victim of Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND), continuing the cycle of disadvantage that began with ESN schools.

I sustain a zero-hour contract job that offers no guaranteed income, supplemented by Universal Credit. My retirement prospects are as bleak as the day I was placed in an ESN school.

E.J.B. Rose Director of the Survey of Race Relations in Britain, foresaw the grim reality we face today as early as 1969, predicting that without radical changes to the educational system, Britain would create a "Black helot class" by the year 2000. Tragically, this prophecy has materialized. It is no longer just a societal issue—it is the reality of my family.

This system, rooted in racism and neglect, tore apart my family. My children have found themselves in prisons, mental health hospitals, and care homes, all institutions shaped by a system that failed us. Now, this same system threatens to snake its way into my grandson's life. Though he is biracial, the fact that he is half white offers no protection; he is treated no differently, targeted by the same prejudices and injustices.

Rising Above: Strength Born from Pain

But make no mistake—this story does not end in despair. Though we have endured immense pain, our wounds do not define us. My children will rise; they will find strength, and they will have the last laugh, and my grandson will achieve greatness in whatever he touches. Because in the end, evil does not win. We carry scars, but we also carry resilience, and that is something no system can take away. Thank you.