Magic

Discover Senate House Library's holdings on the history of magic from the Harry Price Library of Magical Literature.

Click on each image to view the item in more details.

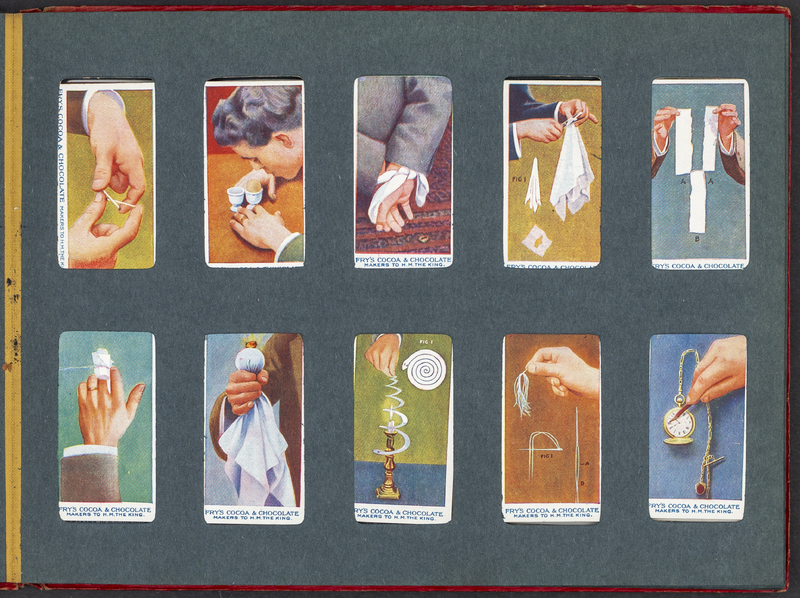

Cigarette cards were a form of trade cards, originally functioning to reinforce cigarette packets but quickly becoming collectable. Companies like confectioner Fry’s produced themed sets like these as promotional tools. Their series of 50 'Amusing tricks and how to do them' feature illustrations with brief descriptions on the reverse.

The Magicians’ Club of London was founded in 1911 by Will Goldston and Harry Houdini, who was elected as its first president. Harry Price initially served as the Club’s Librarian before being elected vice-president on 30 March 1932. The inscription on the back of the medal reads: 'To Harry Price Director of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research London in appreciation of his services to magic from the Council of the Magicians' Club.'

Ira Erastus and William Henry Davenport had a huge influence on 19th century magic and society. From the mid1850s they toured America, and later the world, with their spirit cabinet routine. The Davenports quickly became associated with spiritualism, which was becoming more popular in both America and Britain. The performance was presented as being a genuine supernatural phenomenon. The Davenports’ spirit effects were repeatedly exposed as trickery, but they continued to tour until William Henry’s death in 1877.

The famous 19th century conjuror Bartolomeo Bosco is alluded to here in a satire on King Louis-Philippe from the French magazine La Caricature. The prestidigitator's patter begins with ‘nothing in the hands, nothing in the pockets, nothing in the pistol’ before offering the audience ‘explosion, detonation, conjuration, conspiracy, arrest, emotion, reception, acclamation, deputation, and… amazement!!!’

This colour lithograph print was part of a series depicting scenes of Paris life in the first half of the 19th century. Here a conjuror performs one of the oldest known acts of sleight of hand, the cups and balls, to a larger audience on the streets of central Paris.

This print was the frontispiece of a pamphlet that would have promoted the Mr Henry’s (John Henry Galbreath) performances. Henry was a Scottish or English performer who had appeared at the Lyceum Theatre and Astley’s Amphitheatre in 1788. He toured a show featuring mechanical amusements, conjuring and ventriloquism. It shows the stage layout of an early 19th century magic show, including draped tables to conceal assistants. Mr. Henry stands at the centre, holding a broken bottle that has just released a live bird.

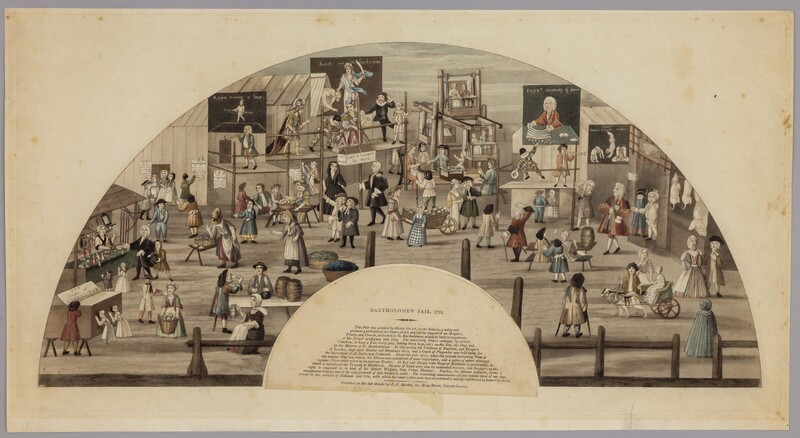

An enlargement of detail of Isaac Fawkes, an 18th century conjuror, from a print depicting Bartholomew Fair. Fawkes is shown performing the Egg Bag trick, in which a multitude of eggs are produced from an empty bag.

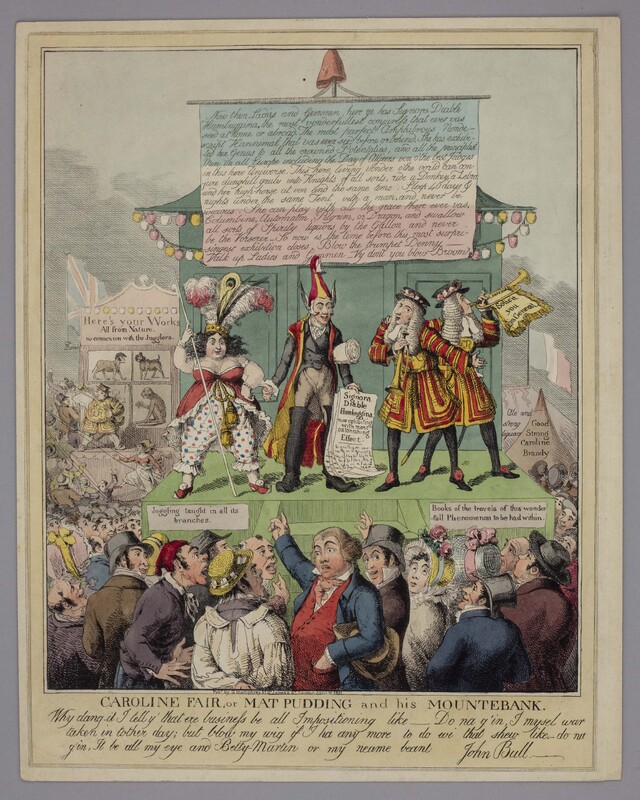

A coloured print of an etching depicting conjuror’s booth at a fair as a satirical attack on Caroline of Brunswick, here taking the role of a conjures with her supporters Henry Brougham and Thomas Denman in attendance as beefeaters.

A coloured fan print depicting Bartholomew Fair, one of London’s oldest summer charter fairs, in 1721. Starting in 1133, the annual Fair took place for three days around St Bartholomew’s Day. Its original purpose was as a cloth fair, but it is best known as a pleasure fair, offering its visitors a range of popular entertainments. To the right is the booth of Isaac Fawkes, the most popular conjuror of his day.

A conjuror performs tricks, including cups and balls, for the amusement of a mixed audience in a salon or parlor. A small animal is included as one of the items emerging from the cups.

Carl Devo was the stage name of Will Goldston, the prolific writer and publisher of guides, biographies, histories and manuals of magic. Goldston began performing at the age of 16 with a ‘black art’ act, as this poster advertises. The act involved using partially black props in front of a black background to create illusions.

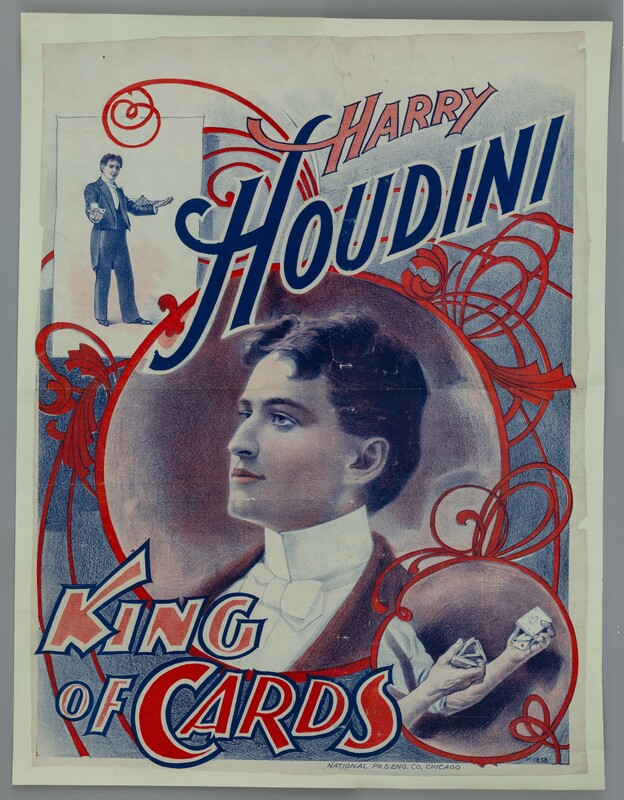

This poster promotes a young Harry Houdini as the ‘King of Cards.’ Houdini’s career began with card magic, but his fame came chiefly from his later performances of feats of escapology and grand stunts, such as making an elephant vanish from the stage of the New York Hippodrome.

This poster advertises a variety bill at the Surrey Theatre, a music hall in south London which started life as a circus in the late 18th century and became a dramatic and variety theatre in the 19th century. The main attraction is the ‘Egyptian’ magician The Great Rameses, the stage name of Polish-British performer Albert Marchinski. He was a specialist in large scale illusions as depicted in the poster.

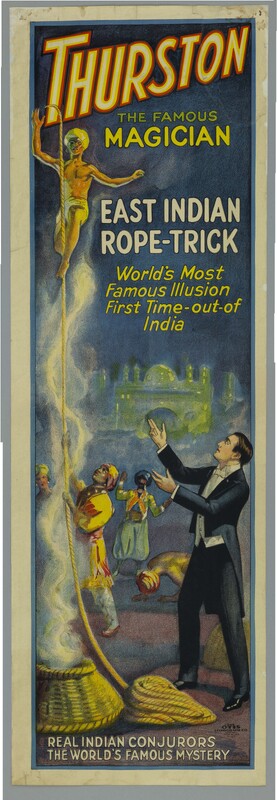

The great American magician Howard Thurston travelled in India in the early 20th century, performing and investigating Indian magic. He never discovered the truth of the legendary Indian Rope Trick, but it was a mainstay of his magic act, which would become one of the biggest touring shows in America. Thurston’s posters are among the most iconic of the golden age of magic, and the typography, design and artwork have come to define the aesthetic of classical conjuring.

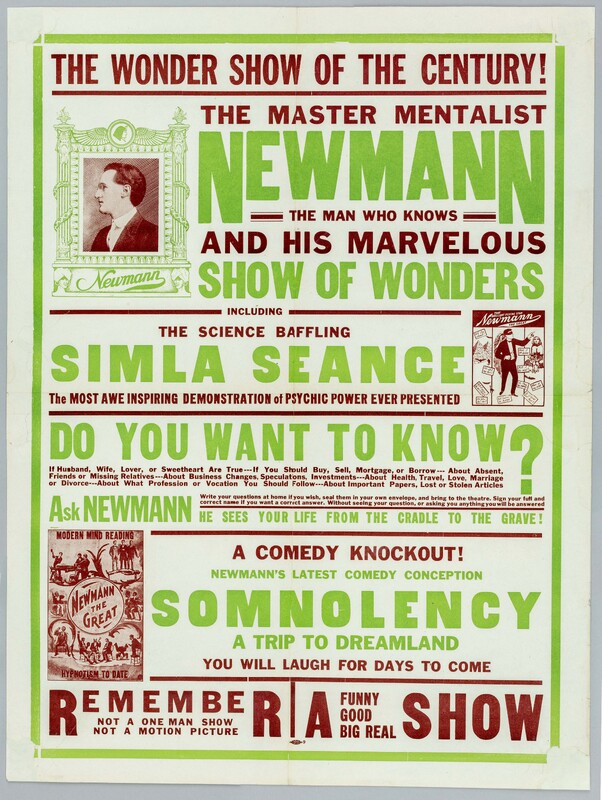

C.A. Newmann, or Newmann the Great was an American stage hypnotist and mentalist whose performances featured highly skilled acts of mind reading and telepathy. Newmann began performing as a teenager in the 1890s and continued to perform until a few years before his death in 1952.

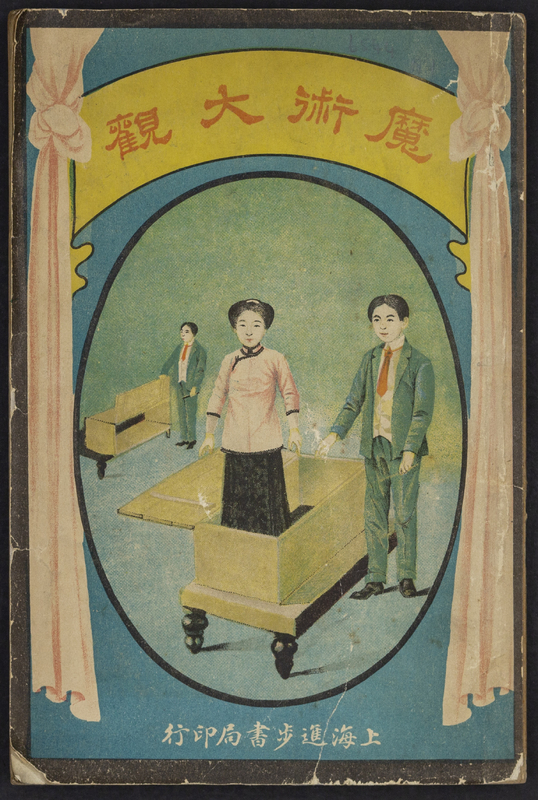

This book (Translated title: The devil's art from top to bottom: Exhaustive Exposé of Magic) features many tricks from western conjuring manuals including magic lanterns, optical illusions, trick tables, the Sphinx, the Cabinet of Proteus and handkerchief and coin magic. The cover shows a trunk transposition, with the female performer being locked in one trunk and then appearing from another.

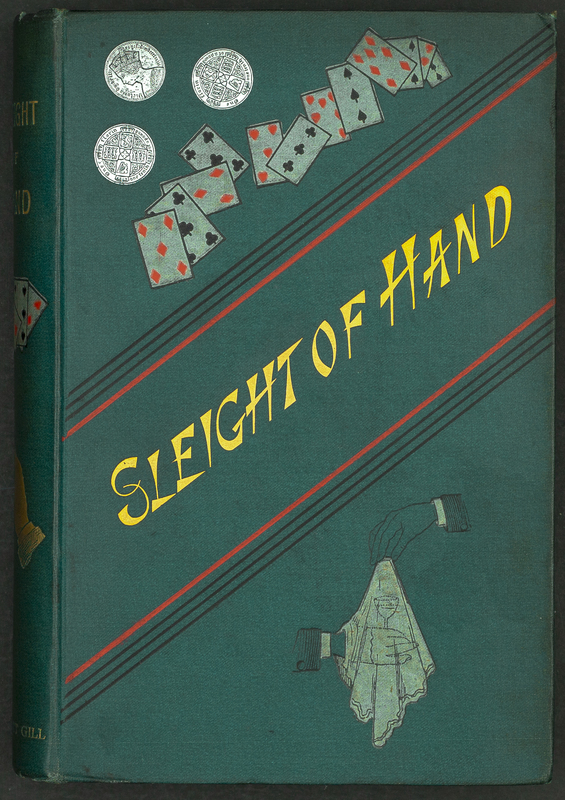

This book from the Harry Price Library describes the skills required for sleights and misdirection used in drawing room magic, the performance space of most amateur magicians, and in ‘grand magic’ for the stage. It began as a series of articles in the Bazaar Exchange and Mart before being collected in a book in 1877.

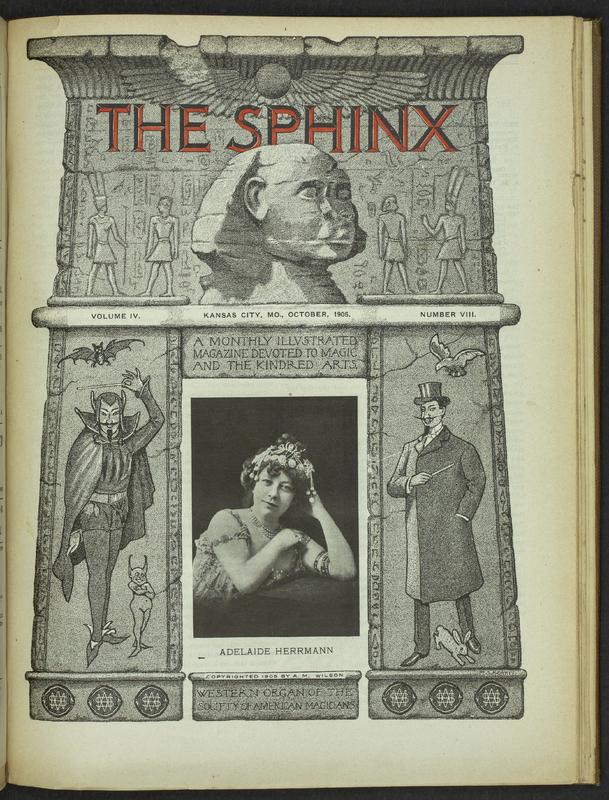

Women in magic are often in a minority and overlooked. Adelaide Herrmann, known as the Queen of Magic across America, was renowned for her version of the bullet catch trick and skill with billiard balls. She featured often in the magical and popular press and appears here on the cover of The Sphinx.

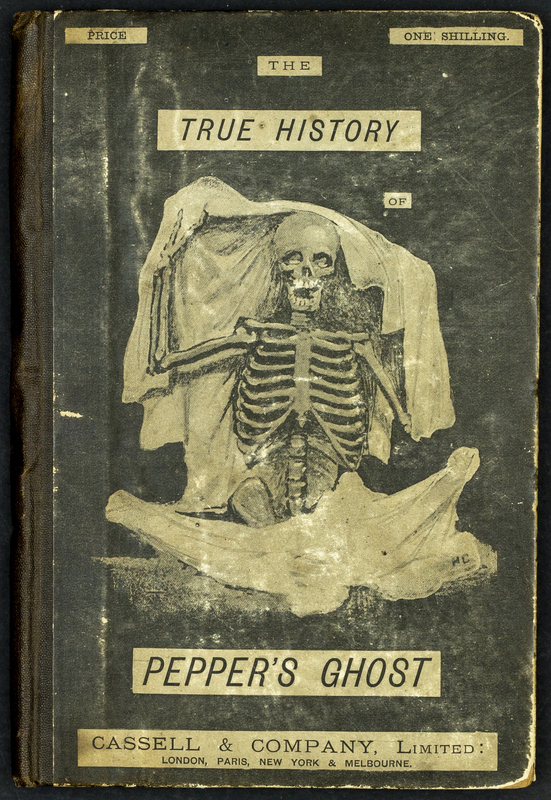

Pepper’s Ghost was a sensation of the Victorian age: an optical illusion that produced the image of a ghost onstage through a combination of light and reflections through glass. Attributed to Henry Dircks, the invention showed the usefulness of glass in creating stage illusions. This book tells the story of the full history of the effect's origin and development.

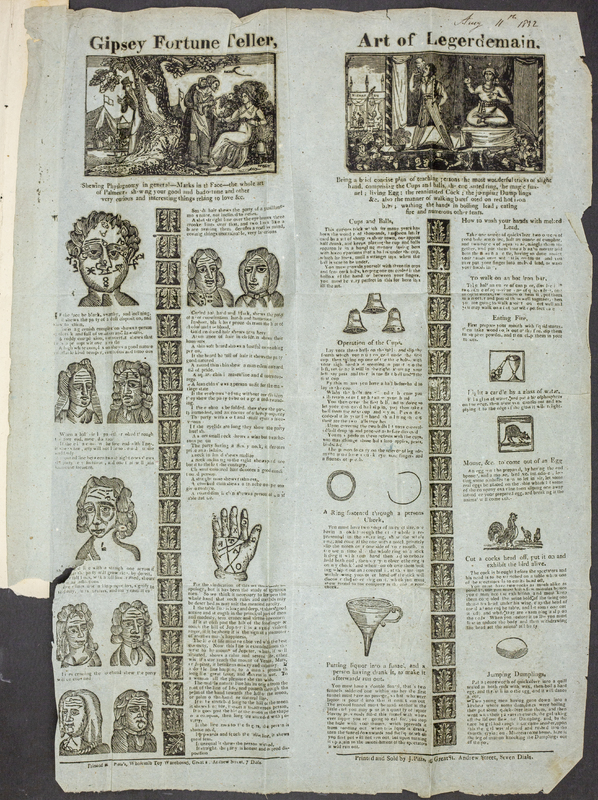

Printed on one side of a single sheet, this article gives concise instructions in learning the arts of conjuring, including the cups and balls, decapitating and reviving a cockerel, and stunts such as walking on hot iron bars and fire-eating. Broadsides or broadsheets were produced as cheaply as possible as forms of mass entertainment, as such they were ephemeral and can be incredibly rare. It was printed with the Gypsey Fortune Teller, revealing the secrets of physiognomy and palmistry.

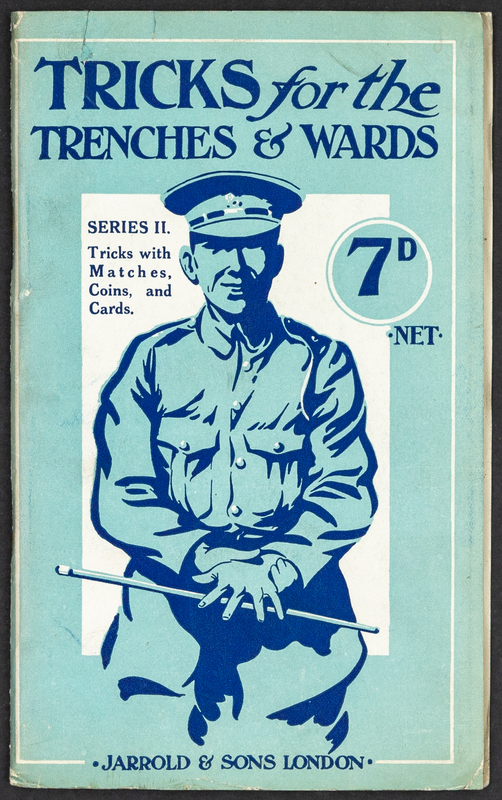

Written by Charles Folkard, professional magician and illustrator, under the pseudonym Draklof, this was a popular series of two pamphlets containing simple tricks with basic props, such as matches and coins that could be mastered easily and performed by a nurse or soldier.

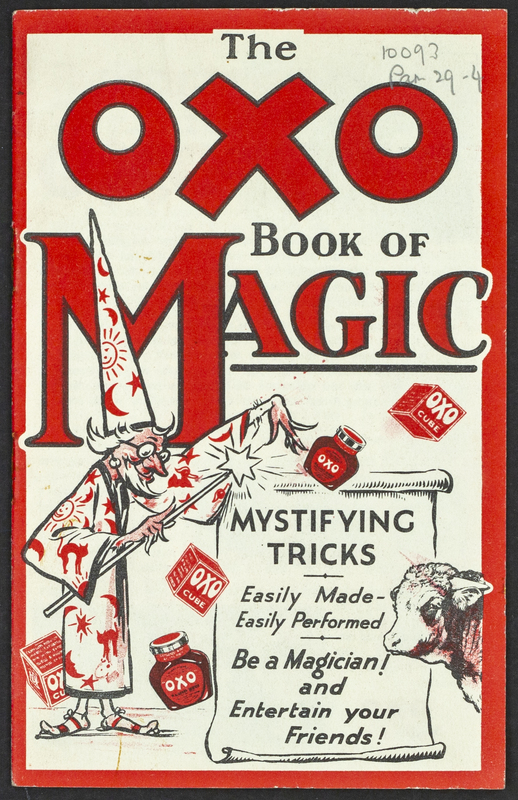

This small pamphlet re-purposes simple, classic tricks for use with Oxo products and packaging - an example of using magic for advertising and promotion. It was sent to several magic magazines and received positive mentions, for the potential of its wide distribution to stimulate interest in magic and as an advertising gimmick.

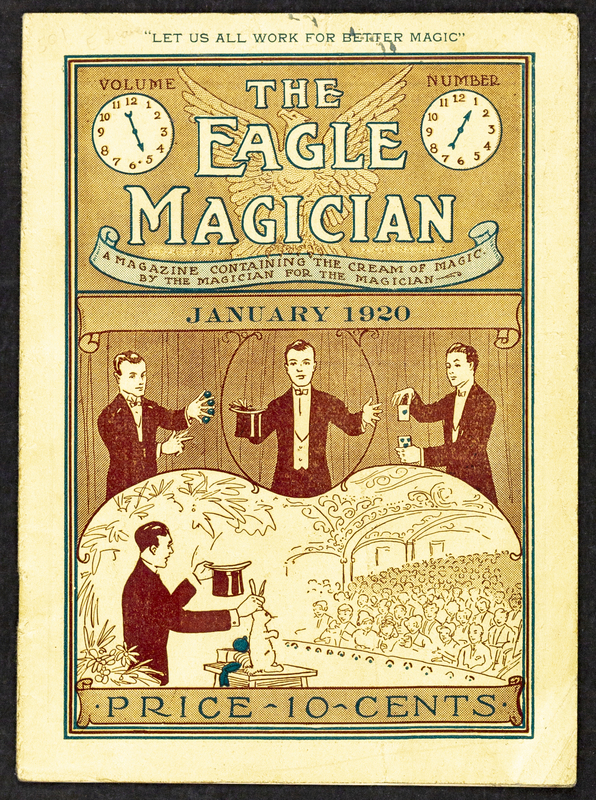

This periodical was published between 1915 and 1922 by Collins Pentz in Minnesota. Pentz started in magic as a dealer and inventor of magic effects, establishing a mail order company in 1896 before creating the Eagle Magic Factory in 1901, as well as organising several magic clubs. The journal covered tricks and advice for professional and amateur magicians.

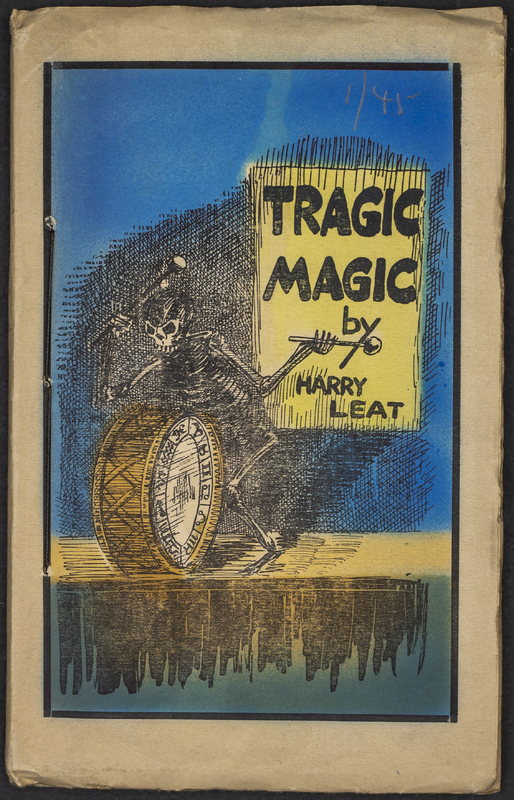

This pamphlet of magical miscellany uses some interesting imagery on its wrappers. Skeletons are commonly used in magic, but the combination with a drum, bearing symbols similar to those used in the Magic Circle logo, conjures up ideas of mortality and death. Harry Leat was an author and dealer of magic books and equipment. He was also known for his outspoken criticism of some of his colleagues, which is included in this book.

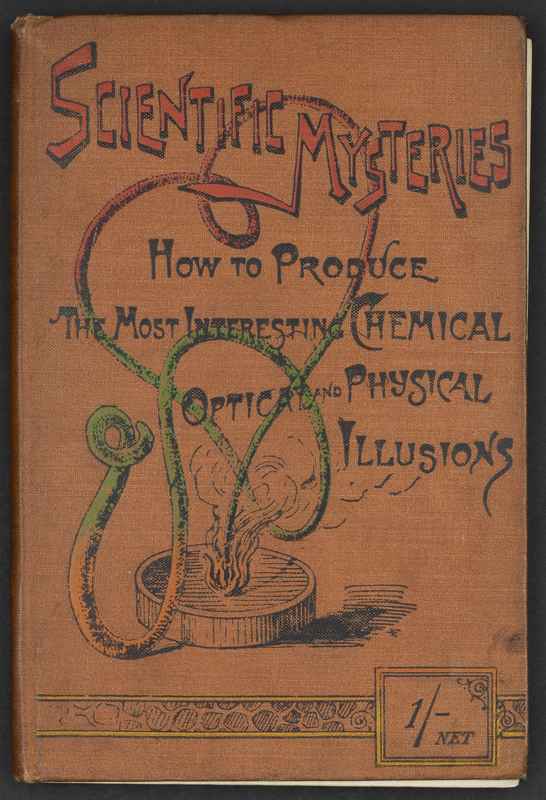

A later book that combines magic and scientific experiments. Experiments with gases, phosphorus, metals, crystallisation and even ‘nihilist bombs’ are alongside invisible inks, inexhaustible bottles, colour changing flowers and the diving imp, often featured in early conjuring books. Important optical illusions of 19th century theatre are also present: stage ghosts, a version of Pepper’s ghost using glass to reflect an actor's image onto the stage and ‘decapitation no murder’.

This little book combines legerdemain, scientific curiosities, feats of strength and accounts of unexplained phenomena. Although this book is rare, books combining these subjects as amusements for readers were common in the late 18th and early 19th century, popularising both magic and experiments in chemistry and physics.

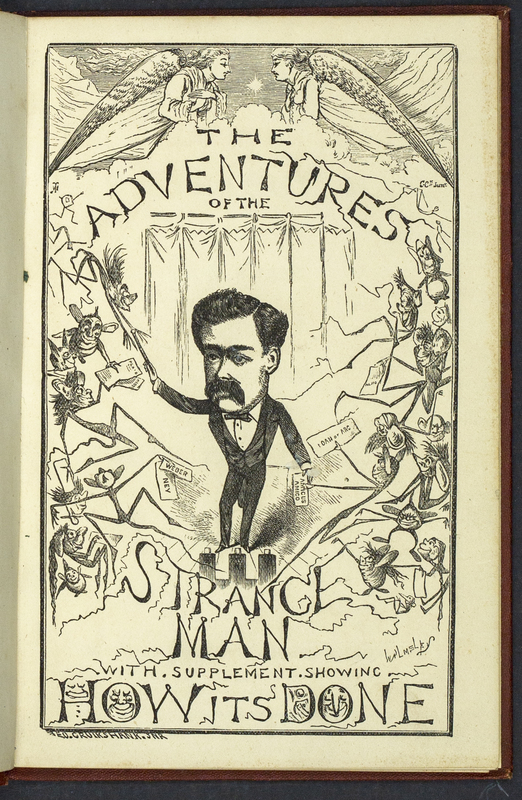

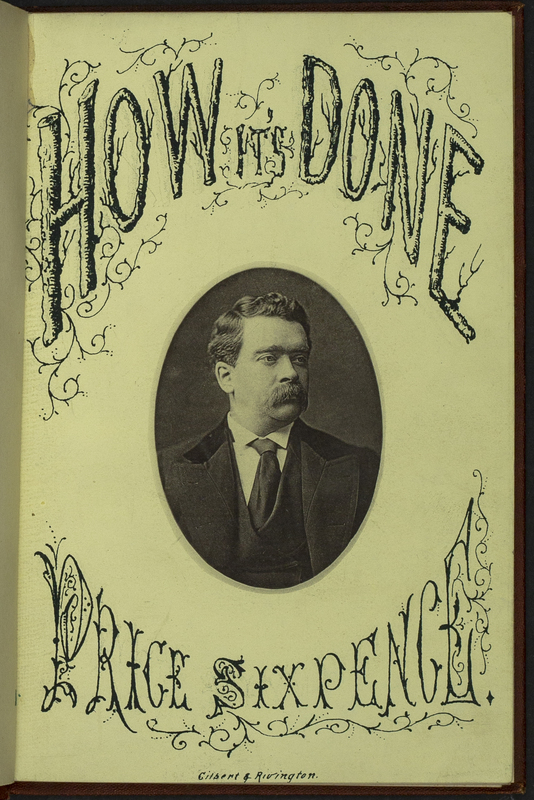

Dr Hugh Simmons Lynn toured many countries and this book, with a frontispiece by George Cruickshank Jr, records his adventures. Lynn was possibly the first to perform the Japanese Butterfly Trick in the West in 1864, and from 1873 he performed a wide-ranging magic show at the Egyptian Hall. Lynn’s patter included the phrase ‘that’s how it’s done’ and it became a popular catch phrase, no doubt helped by this book.

Dr Hugh Simmons Lynn toured many countries and this book, with a frontispiece by George Cruickshank Jr, records his adventures. Lynn was possibly the first to perform the Japanese Butterfly Trick in the West in 1864, and from 1873 he performed a wide-ranging magic show at the Egyptian Hall. Lynn’s patter included the phrase ‘that’s how it’s done’ and it became a popular catch phrase, no doubt helped by this book.

The cover and author of this book allude to Harry Kellar, the “Dean of American Magic” and his illusion the “the levitation of Princess Karnac.” It’s unlikely the Prof. Keller of the book is the same great magician: it was actually an American reprint of Robert Ganthony's "Bunkum Entertainments", published in London in 1895. The book features a small section on conjuring along with fortune telling, mind reading, physiognomy, juggling, phrenology, phonography and ventriloquism.

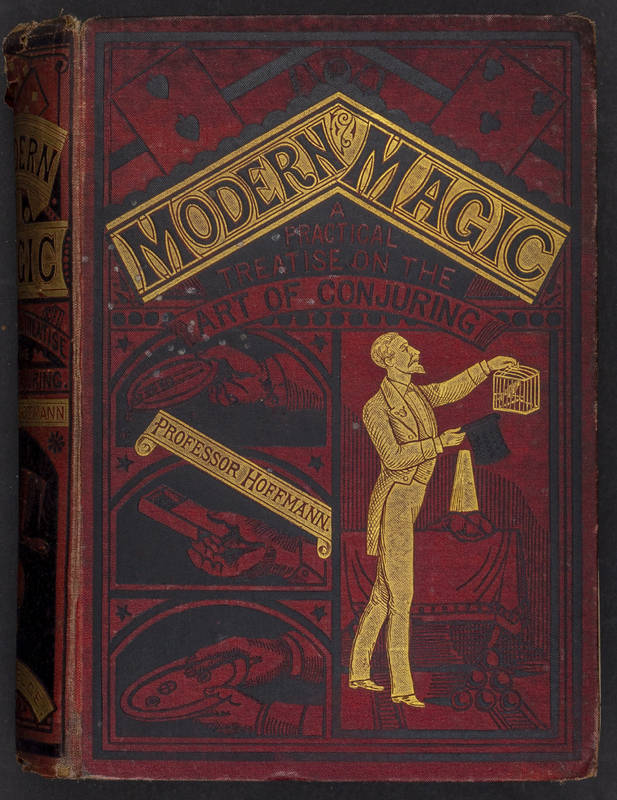

Modern Magic is a landmark in magic books. Published in successive editions, it was the first in a tetralogy of books - More Magic (1890), Later Magic (1903) and Latest Magic (1918) - that for the first time attempted to create an encyclopaedic and instructional book of performance magic. It became a textbook for aspiring magicians and a record of the contemporary practice of magic.

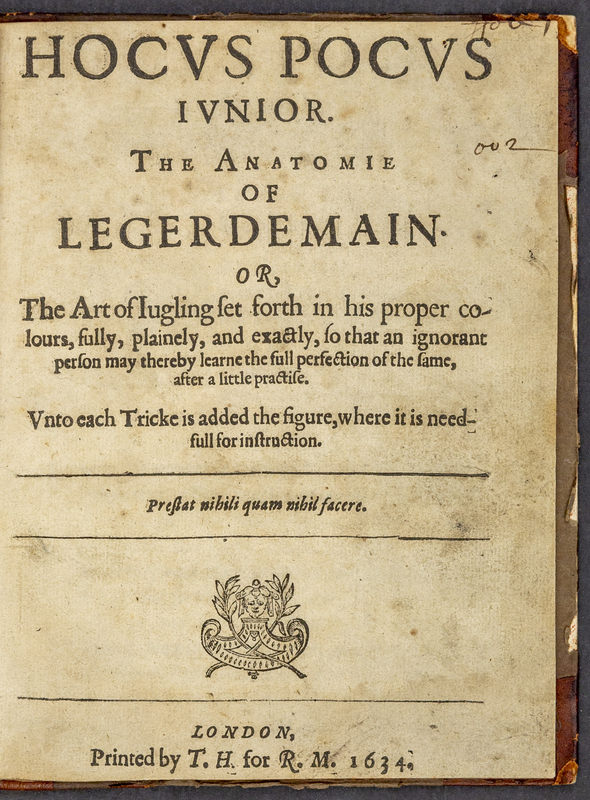

This is the earliest illustrated English book devoted to conjuring, covering the usual tricks with cups and balls, coins, cards and confederates. The man behind the book may have been William Vincent, licensed under King James I to ‘exercise the art of Legerdemaine’. He became known as ‘the King’s most excellent Hocus Pocus.’

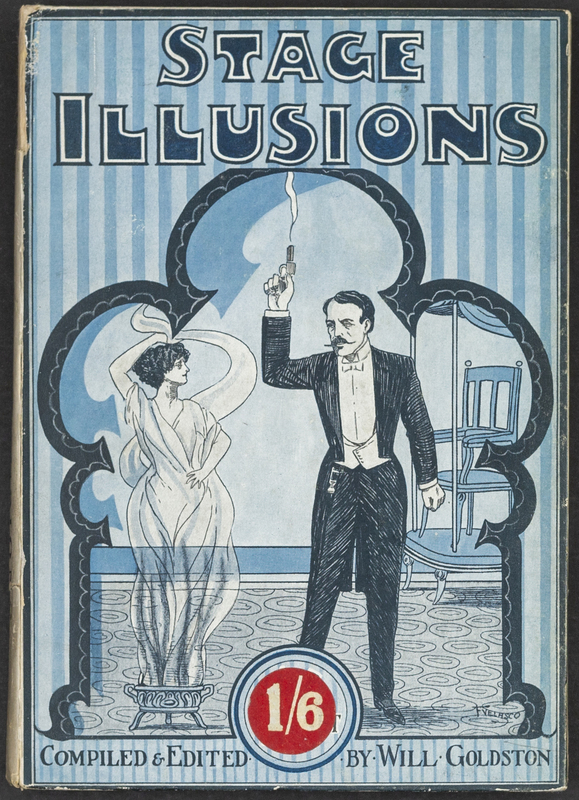

Will Goldston was a prolific writer and publisher of guides, biographies, histories and manuals of magic, who also had a short-lived stage career performing a black art act under the name Carl Devo. After leaving the Magic Circle in 1911, he founded his own society, Magicians' Club of London. Goldston wrote and published many books revealing magicians’ secrets. This book, largely compiled from material in magazines, reveals the mechanics behind illusions.

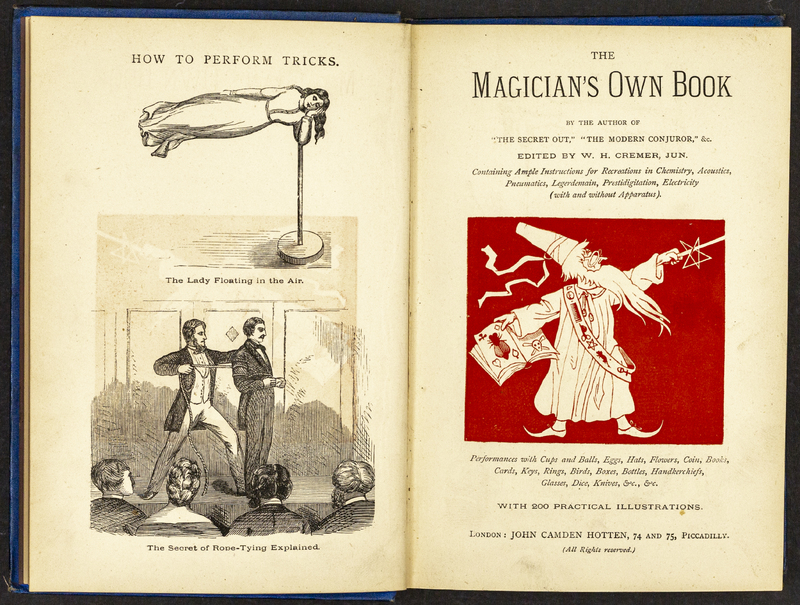

This compendium of magic tricks and illusions draws heavily on earlier American conjuring books with some additions. The illustrations on the frontispiece featuring acts that were common in the performances of European conjurors, such as Robert-Houdin, but that also have roots in Indian magic.

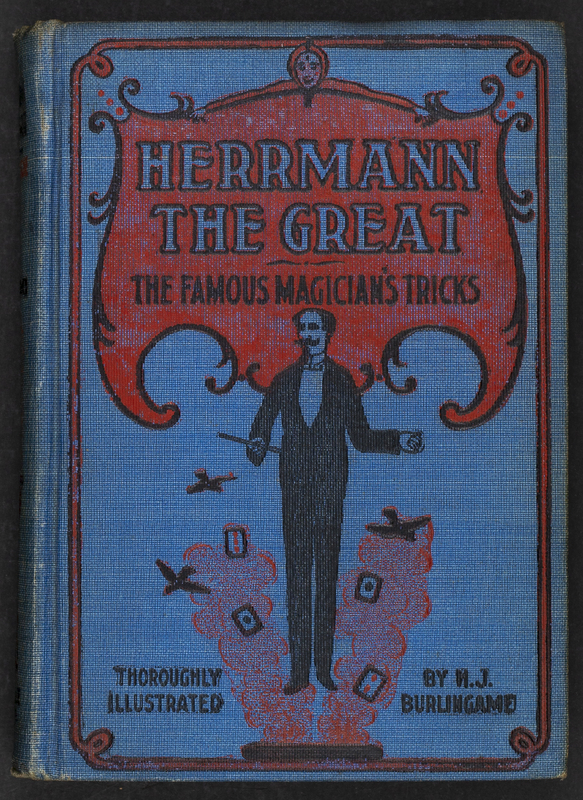

Alexander Herrmann was part of a dynasty of French magicians who had his greatest success on the American stage. Herrmann’s shows were particularly noted for their humour and his showmanship. He was one of the few magicians to actually pull a rabbit from a hat.

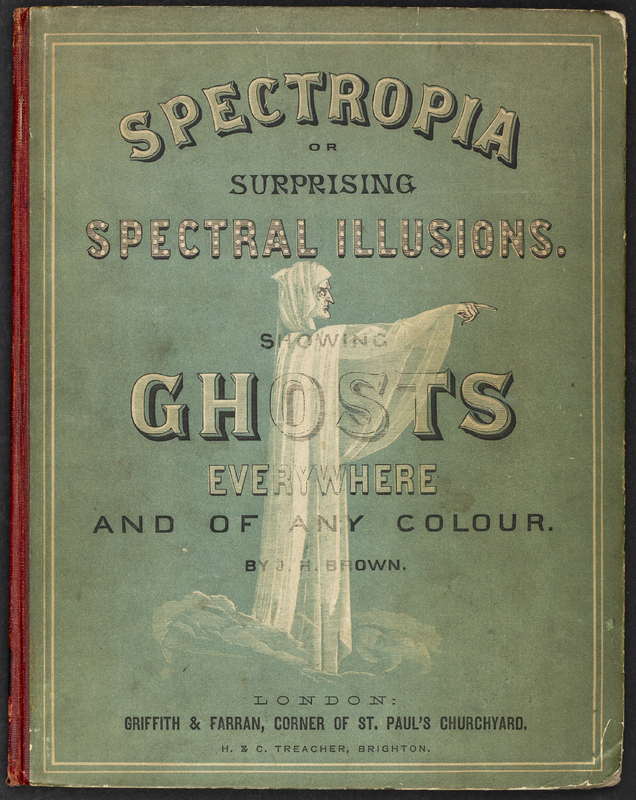

This book allowed the reader to create optical illusions of ghostly figures, a common feature of 19th century magic acts. The book came with a scientific explanation of the afterimage effect that it uses to create optical illusions. The author hoped it would help combat superstitious beliefs that such apparitions were genuine ghosts.

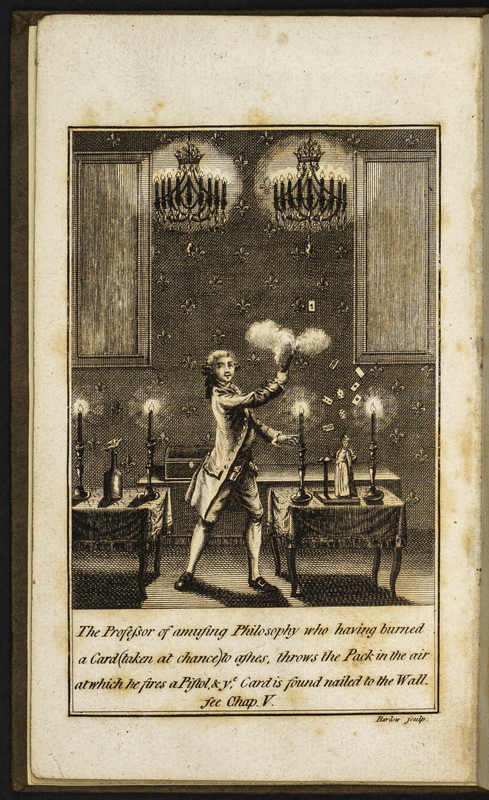

This book was first published in French in 1784 as La Magic Blanche Dévoilée. Decremps’s aim was to expose what he saw as the fraud of performers who profited from their audience’s ignorance rather than to train his readers in performing tricks themselves. This frontispiece depicts a version ‘The card nailed to the wall with a pistol shot’ which involves the conjuror firing a nail at a pack of cards that have been thrown into the air and skewering the card selected by the audience.

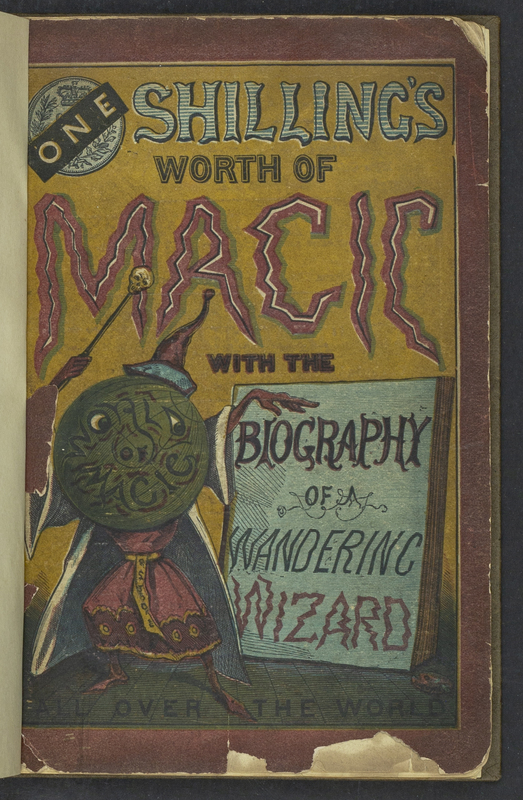

The roles of boys and girls became more defined in the early 19th century and began to diverge from each other. Books like this were intended for boys who attended school, rather than work, to ensure they used their leisure time productively. Conjuring became a key part of these books alongside other indoor and outdoor pursuits. It was considered a fitting diversion for an ingenious to boy to entertain themselves and their friends.

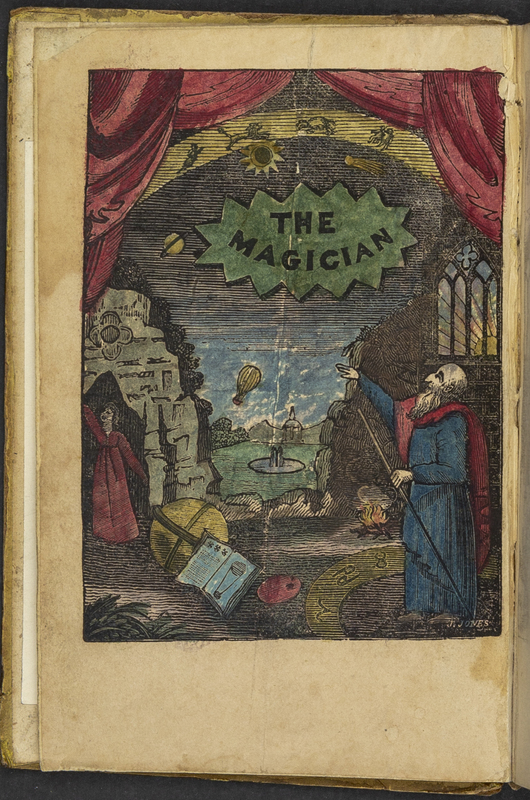

This chapbook, a small cheaply produced paper-covered booklet, takes its content from many other guides to the conjuring arts from the late 18th and early 19th century. The book was aimed at children, with an advertisement on the back cover offering ‘children’s books, one penny each’ from the publisher, Thomas Richardson.

John Henry Anderson is one of the first great names of modern magic. He claimed that the title of ‘The Great Wizard of the North’ was conferred on him by Sir Walter Scott. His belief in the importance of creating a performance that was entertaining and dazzled the audience rather than just being a demonstration of skill helped established magic as an important fixture of the stage.

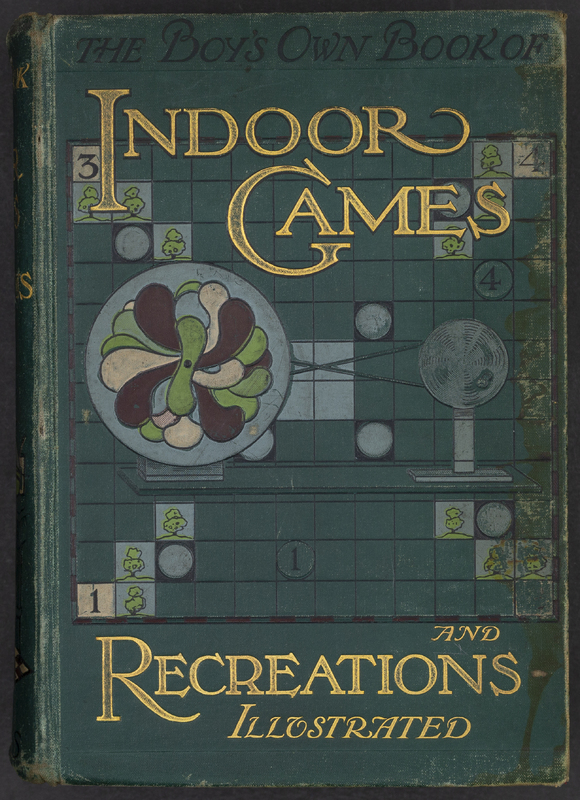

The book comes from the tradition of newspapers, magazines, journals and books for boys with amusement and entertainment for their leisure time. Boy’s Own publications began to appear in the mid-19th century in America and Britain and featured stories, activities, sports and hobbies. This extensive book focuses on activities that boys could do at home, particularly involving building their own apparatus. It covers conjuring, experiments, board games among many other activities.

Interested in Magic and the Paranormal? Find out more in our Paranormal, Occult and Magical digital collection